Thursday, September 28, 2006

Monday, September 11, 2006

Gayatri Mantra

"Om bhur'bhuvah svah tatsaviturvarenyam bhargodevasya dhimahi dhiyo yo nah prachodyat"

Om ~ Brahma or Almighty God

bhuh ~embodiment of vital spiritual energy (Pran)

bhuvah~destroyer of sufferings

svah~embodiment of happiness

tat ~that

savituh~bright, luminous like the Sun

varenyam~best, most exalted

bhargo~destroyer of sins

devasya~divine

dhimahi~may imbibe

dhiyo~intellect

yo ~who

nah ~our

prachodyat~may inspire

In short it is a prayer to the Almighty Supreme God, the Creator of entire cosmos, the essence of our life existence, who removes all our pains and sufferings and grants happiness beseeching His divine grace to imbibe within us His Divinity and Brilliance which may purify us and guide our righteous wisdom on the right path. A man gets imbued with divine qualities contemplating and meditating on this meaning of Gayatri. One should contemplate on these feelings daily and regularly. Three prayer-filled meditations are given here which should be silently recited and projected on the mental screen through imagination.

1. “The Almighty God, who is known as pranav pervades all the three Lokas, viz, Bhooha-lok, Bhuvaha-lok and Swaha-lok. He is Omnipresent. The cosmos is physical manifestation of God who pervades its each and every particle. I am seeing Him everywhere. I would always refrain from evil thoughts and evil deeds and perform true worship of God by extending cooperation in promoting happiness, peace and beauty in this universe which is His creation”.

2. “This (tat) God is extremely bright (savitur), most exalted (varenyam), devoid of sin (bhargo) and divine (devasya). I visualise this Divinity within me, in my soul. By such contemplation, I am becoming illumined, virtues are growing in all the layers of my being. I am being saturated with these virtues, these characteristics, of God.”

3. “That God may inspire (prachodayat) our (naha) intellect, wisdom (dhiyo) and lead us on righteous path. May our intellect, the intellects of our family members and of all of us, be purified and may He lead us on the righteous path. On getting righteous wisdom, which is the greatest achievement and is the source of all the happiness in this world, we may be able to enjoy celestial bliss in this life and make our human life purposeful.”

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

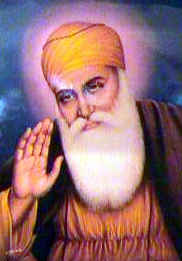

Facts and Stats on Sikhism

Facts and Stats on Sikhism

name ::From Punjabi sikh, "learner" or "disciple"

founded c. 1500 in India

founder ::Shri Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1538)

adherents:: 23 million

main location:: Punjab region of India

original language ::Punjabi

sacred text ::Adi Granth (Sri Guru Granth Sahib)

spiritual leaders ::Granthi, giani

house of worship ::Temple, gurdwara

theism ::monotheism

ultimate reality ::God (Ik Onkar, Nam)

purpose of life ::Overcome the self, align life with will of God, and become a "saint soldier," fighting for good

afterlife ::

Reincarnation until resolve karma and merge with God.

major holidays ::Vaisakhi DayBirthday of Guru NanakBirthday of Guru Gobind Singh

five cardinal vices

1. lust2. anger3. greed4. worldly attachment5. pride

Something About Sikhism

The word "Sikhism" derives from "Sikh," which means a strong and able disciple. There are about 23 million Sikhs worldwide, making Sikhism the 5th largest religion in the world. Approximately 19 million Sikhs live in India, primarily in the state of Punjab. Large populations of Sikhs can also be found in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. Sikhs are a significant minority in Malaysia and Singapore, where they are sometimes ridiculed for their distinctive appearance, but are respected for their work ethic and high education standards.

Sikhism emerged in 16th-century India in an environment heavily permeated with conflicts between the Hindu and Muslim religions. It was somewhat influenced by reform movements in Hinduism (e.g. Bhakti, monism, Vedic metaphysics, guru ideal, and bhajans) as well as some Sufi Muslim influences. While Sikhism reflects its cultural context, it certainly developed into a movement unique in India. Sikhs regard their faith as an authentic new divine revelation.

Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak Dev, who was born in 1469 to a Hindu family. After four epic journeys (north to Tibet, south to Sri Lanka, east to Bengal and west to Mecca and Baghdad), Guru Nanak preached to Hindus, Muslims and others, and in the process attracted a following of Sikhs (disciples). Religion, he taught, was a way to unite people, but in practice he found that it set men against one another. He particularly regretted the antagonism between Hindus and Muslims. Guru Nanak's most famous saying is, "There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim, so whose path shall I follow? I shall follow the path of God."

Retaining the Hindu doctrine of the transmigration of souls, together with its corollary, the law of karma, Guru Nanak advised his followers to end the cycle of reincarnation by living a disciplined life – that is, by moderating egoism and sensuous delights, to live in a balanced worldly manner, and by accepting ultimate reality. Thus, by the grace of Guru (Gurprasad) the cycle of reincarnation can be broken, and the Sikh can remain in the abode of the Love of God. Guru Nanak taught that salvation does not mean entering paradise after a last judgment, but a union and absorption into God, the True Name. Sikhs do not believe in a heaven or hell. Sikhs also reject the Hindu belief in incarnations (avatars) of God, believing instead that God makes his will know through the Gurus.

The most easily observable Sikh practices are the wearing of the turban and the Five Ks. Sikhs also pray regularly and meditate by repeating God's name, often with the aid of rosary beads. Sikhism rejects the Hindu notion of the four stages of life, teaching instead that the householder is the ideal for all people. A Sikh aims to live a life that balances work, worship and charity. Community is emphasized, and the Sikh temple (gurdwara) is the center of Sikh communal life.

Something about our Vedas

The Vedas

The most sacred scriptures of Hinduism are the Vedas ("Books of Knowledge"), a collection of texts written in Sanskrit from about 1200 BCE to 100 CE. As sruti, the Vedas are regarded as the absolute authority for religious knowledge and a test of Hindu orthodoxy (both Jains and Buddhists reject the Vedas).

"For Hindus, the Veda is a symbol of unchallenged authority and tradition."

{1} Selections from the Vedas are still memorized and recited for religious merit today. Yet much of the religion presented in the Vedas is unknown today and plays little to no role in modern Hinduism.

As historical and religious literature often is, the text is written from the perspective of the most powerful groups, priests and warrior-kings. Scholars say it is therefore unlikely that it represents the totality of religious belief and practice in India in the first millennium BCE. This perspective is especially evident in the earlier parts of the Vedas, in which the primary concerns are war, rain, and dealing with the "slaves," or native inhabitants of India.

Initially, the Vedas consisted of four collections of mantras (Samhitas), each associated with a particular priest or aspect of ritual:

Rig Veda (Wisdom of the Verses); Sama Veda (Wisdom of the Chants); Yajur Veda (Wisdom of the Sacrificial Formulas); and Atharva Veda (Wisdom of the Atharvan Priests).

Over the centuries, three kinds of additional literature were attached to each of the Samhitas: Brahmanas (discussions of the ritual); Aranyakas ("books studied in the forest"); and Upanishads (philosophical writings).

In these later texts, especially the Upanishads, the polytheism of the earlier Vedas has evolved into a pantheism focused on Brahman, the supreme reality of the universe. This concept remains a key feature of Hindu philosophy today.

Samhitas As noted above, the Samhitas ("Collections") are the oldest components of the Vedas, and consist largely of hymns and mantras.

There are four Samhitas (also called Vedas): Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, and Atharva Veda.

The Rig VedaComposed as early as 1500 BC, the Rig Veda or Rg Veda ("Wisdom of the Verses") is the oldest of the four Vedic collections and one of the oldest surviving sacred texts in the world. The Rig Veda consists of 10,552 verses (collected into 10 books) of hymns and mantras used by the hotri priests.

The hymns of the Rig Veda focus on pleasing the principal gods Indra (war, wind and rain), Agni (the sacrificial fire), Surga (the sun) and Varuna (the cosmic order) through ritual sacrifices. Along with governing important matters of life such as rain, wind, fire and war, the Vedic gods also forgive wrongdoing (5.85.7) and mete out justice in the afterlife (1.97.1).

Deceased ancestors are able to influence the living (10.15.6), so they are also appeased with rituals (10.15.1-11). The afterlife of the Rig Veda is eternal conscious survival in the abode of Yama, the god of the dead (9.113.7-11). It is the gods, not karma, that are responsible for assuring justice in this life and the next (7.104).

Yajur Veda and Sama Veda Both the Yajur Veda ("Wisdom of the Sacrifical Formulas") and the Sama Veda ("Wisdom of the Chants") are liturgical works consisting primarily of selections from the Rig Veda. The Yajur Veda was used by udgatri priests and contains brief prose to accompany ritual acts, many of which are addressed to the ritual instruments and offerings. The Sama Veda was chanted in fixed melodies by the adhvaryu priests. Each contain about 2,000 verses.

Atharva Veda The Atharva Veda ("Wisdom of the Atharvan Priests) was added significantly later than the first three Samhitas, perhaps as late as 500 BC. It consists of 20 books of hymns and prose, many of which reflect the religious concerns of everyday life. This sets the Arharva Veda apart from the other Vedas, which focus on adoring the gods and performing the liturgy of sacrifice, and makes it an important source of information on the practical religion and magic of the time.

Books 1 through 8 of the Atharva Veda contain magical prayers for long life, prosperity, curses, kingship, love, and a variety of other specific purposes. Books 8 through 12 include cosmological hymns, marking a transition to the loftier philosophy of the Upanishads. The remainder of the books consist of magical and ritual formulas, including marriage and funeral practices.

BrahmanasThe mythology and significance behind the Vedic rituals of the Samhitas are explained in the Brahmanas. Although they include some detail as to the performance of rituals themselves, the Brahmanas are primarily concerned with the meaning of rituals. A worldview is presented in which sacrifice is central to human life, religious goals, and even the continuation of the cosmos.

Included in the Brahmanas are extensive rituals for royal consecration (rajasuya), which endow a king with great power and raise him to the status of a god (at least during the ceremony). Part of the ritual is the elaborate horse sacrifice (asvamedya), in which a single horse is set free, followed and protected by royal forces for a year, then ritually sacrificed at the royal capital.

Aranyakas ("Forest Books") The Aranyakas contain similar material as the Brahmanas and discuss rites deemed not suitable for the village (thus the name "forest"). They also prominently feature the word brahmana, here meaning the creative power behind of the rituals, and by extension, the cosmic order.

Upanishads ("Sittings Near a Teacher") The word "Upanishad" means "to sit down near," bringing to mind pupils gathering around their teacher for philosophical instruction. The Upanishads are philosophical works that introduce the now-central ideas of self-realization, yoga, meditation, karma and reincarnation.

The theme of the Upanishads is the escape from rebirth through knowledge of the underlying reality of the universe. The Encyclopaedia Britannica explains how this change in perspective came about:

Throughout the later Vedic period, the idea that the world of heaven was not the end-and that even in heaven death was inevitable-had been growing. For Vedic thinkers, the fear of the impermanence of religious merit and its loss in the hereafter, as well as the fear-provoking anticipation of the transience of any form of existence after death, culminating in the much-feared repeated death (punarmrtyu), assumed the character of an obsession. The older Upanishads are affixed to a particular Veda, but more recent ones are not. The most important Upanishads are generally considered to be the Brhadaranyaka ("Great Forest Text") and the Chandogya (pertaining to the Chandoga priests). Both record the traditions of sages (rishis) of the period, most notably Yajñavalkya, who was a pioneer of new religious ideas. Also significant are:

Mandukya Upanishad ,Kena/Talavakara Upanishad ,Katha Upanishad ,Mundaka Upanishad Aitareya Upanishad, Taittiriya Upanishad, Prashna Upanishad ,Isha Upanishad Shvetashvatara Upanishad